Chimeras, Unicorns and silly Things

In our conversation, Irène Hug invites us not to take everything as seriously as it may appear. In stark contrast to clean, laconic American minimalist and conceptualist approaches, Hug’s boldly colourful objects, paintings and photographs in tightly packed spaces bombard us with messages about the important things in life. The Swiss artist, who resides in Berlin, wittily undermines our faith in the objective world (and its depiction) and urges us to grasp the deeper meaning of things and words hidden behind their external image. Only universal doubts that strip away the world’s surface layer can facilitate deeper understanding and an uninterrupted process of learning. Only through perpetual doubt can we see things anew and use language to rediscover the world again and again, undergoing an endless cycle of doubt and redefinition. Language is Hug’s main cognitive working tool, and its meaning transcends the limits of using language as a tool.

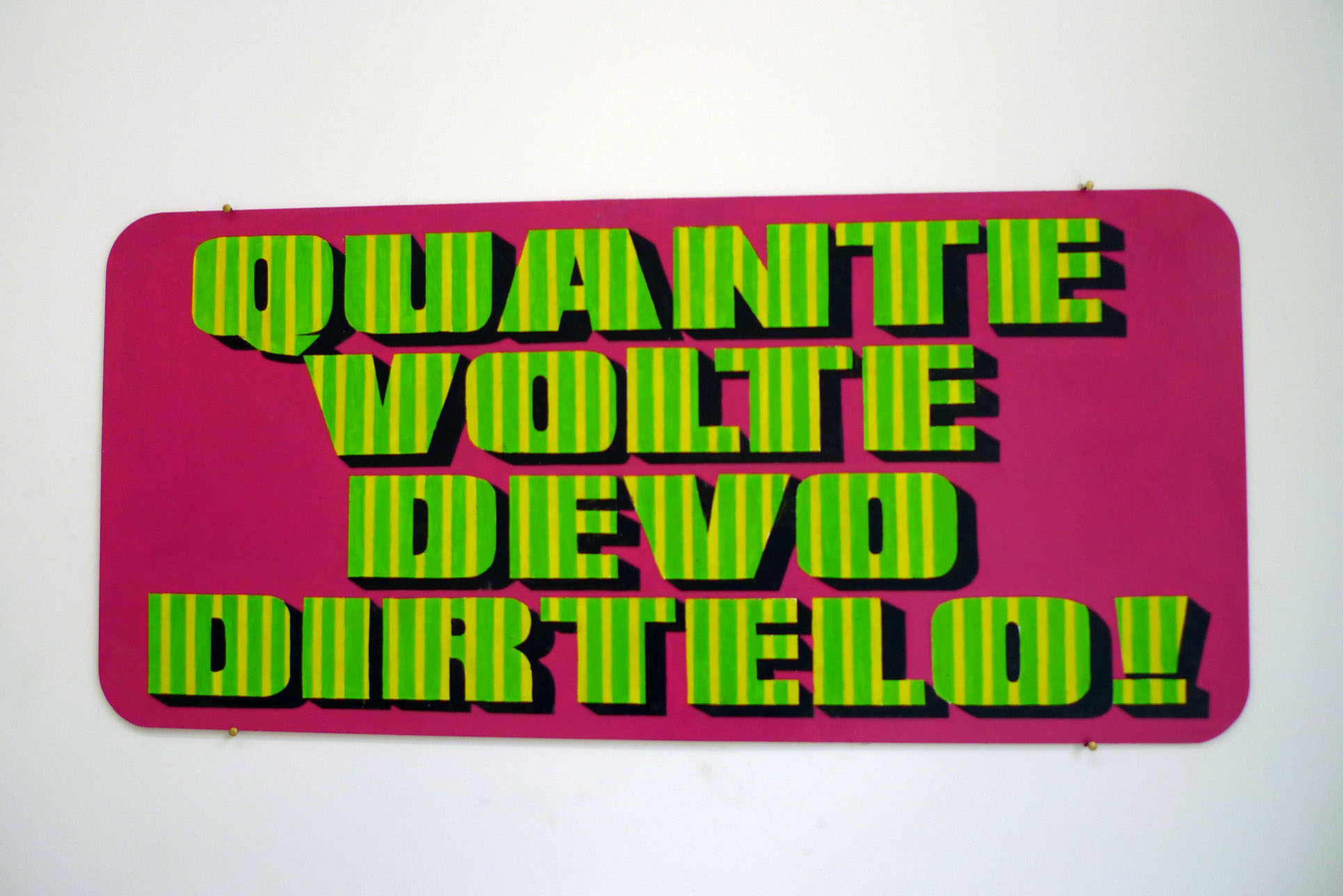

For Hug, words that hint at language itself grow out of space and scream at us at full volume to explain that every word and therefore any assignation of meaning to the world is entirely created by humans, and beyond the boundaries of language the world evaporates into thin air. The shadows of the potted plants magically create words that once again brutally reveal the illusion: Don’t take it as read. Only Silly Things, Fatal Statement or in the best case Substitute remain without shadows: language as a substitute for the things it names or art as a substitute for a substitute or a copy of a copy.

Barbara Fässler: Is the world entirely composed of deceptions, a human construct?

Irène Hug: Whether the whole world is a deception I cannot say, but it is certainly the product of human imagination. I am a human being and see the world through human eyes. Everything that we perceive and imagine is solely from the human viewpoint. Therefore I will see the world from my human observation tower, while a tiger or a snail would probably see another world.

B.F.: So the world is not a deception?

I.H.: Deceptions relate to whether something is true or imagined. I tend to think that everything is imagined.

B.F.: Is that why ergo sum (‘therefore I am’) is written beneath your unicorn?

I.H.: When I imagine and create a unicorn, it also exists in reality; that is this unicorn of organic glass and aluminium.

B.F.: And the positioning of the letter sculpture Silly Things right beside your gallery owner’s desk – surely this isn’t a coincidence? Is this a dig at the art market, the art world or even your own art?

I.H.: I won’t say anything about that in public, because there may be grave consequences. I’ll let my gallery representative comment on this, as he has seen the message and understood what it means, and has already issued a brief statement.

B.F.: But is art a form of reality or its Substitute? By that I mean your letter sculpture which forms this word.

I.H.: I can only say what the work Substitute means to me. The question of what it means to art as a whole is too broad. The sculpture is formed from three-dimensional letters made from re-cycled wood. Letters, even printed ones, have always been associated for me with something practical. For me, written text is not just the surface, but the object itself. I emphasise this aspect in my work by giving words a spatial dimension, so that they become present in space. Wood previously used in furniture makes the letters look like furniture. They are piled one on top of another, like tables and chairs before the floor is mopped. Words in themselves are substitutes for what they designate. The word ‘table’ is not the same thing as a table. Words form sounds, which in combination form meaning, for example ‘table’ or ‘substitute’. Unlike ‘table’, Substitute creates and substitutes itself.

B.F.: Is it possible to say that a word is a substitute for the object or concept it describes?

I.H.: A small detour into linguistics: a word consists of letters. Letters are abstract signs designating sounds which when “correctly” joined create a word and its meaning, for example, ‘table’. But the word ‘table’ is not the same as a table – it is a table substitute, a replacement. In the case of the sculpture Substitute it works as follows: it replaces the replacement. A sort of thought-loop sets in. A concept is not the same as a thing, and the image of a thing is not the same as written text. So what really reflects what? This is a common motif in my works: what do signs represent?

B.F.: Does written text reflect or represent reality?

I.H.: Both! It is reality because it is physically present, and it represents the idea expressed in writing.

B.F.: A material or non-material substitute? A reflection or an illusion? In one of your works it is stated: De omnibus dubitandum est (‘Everything must be doubted’). Should we really doubt everything. And if so, then what, in connection with the blank page of this radical scepticism, remains after us in the world? Won’t even reason save us? Here I am referring to your light box Farewell To Reason.

I.H.: My question is not as broad as that – that is your interpretation, which is also possible. You are already touching on the philosophical context. In my photographic works I use Photoshop to change various advertising slogans I find on hoardings. The sentence that you must doubt everything appeared quite un-coincidentally in one of the street scenes. I don’t know Latin, so initially I only understood the word omnibus, which sounded funny to me. Only those who understand the meaning of this sentence in Latin would understand that the sentence could apply to the artwork itself, because the sentences are manipulated and therefore the messages are not real either. Deceptions and their subsequent doubts as a means of transmitting meaning thereby becomes a sort of pathway and form of reading for my works. Therefore, you shouldn’t follow the arrow (Farewell To Reason) and abandon reason!

B.F.: So we must doubt the possibility of truthfully depicting something and the objectivity of photography as such.

I.H.: I am convinced that having doubts is proceeding together with the new opportunities presented by the digital age. In another image there is a sentence that draws attention to this trend: “What is photography?” It can be seen directly above the entrance to the photography store. Doubting is an interesting pastime. It is a precondition for thinking or analysis and was a virtue in the Western world in ancient times and has been again since the 16th century. Doubt is always appropriate. We also doubt when we see one of my images, and the question could be asked what exactly should be doubted there: the corporate logos, the advertising slogans, the origins of the products, the history of the company? Doubts can be read at a number of levels: philosophically, existentially, realistically or in relation to art as such. Utilising doubt in art means very concretely doubting any depiction or artistic expression.

B.F.: With your existential, troubling statements, are you trying to provoke the viewer or liberate them from their consumer existence and encourage active reflection?

I.H.: As long as the viewer perceives that there is something confusing there, something that doesn’t fit the picture because of the language, for example, a sentence in French in a photo from South America, then they should become suspicious and think that something odd is going on. At such moments of confusion, the viewer grows cautious, understanding that something may be amiss, and they start looking for other incompatibilities. I personally like to be a bloodhound and solve mysteries: for example, using Wikipedia to discover who Roxelane was. What did that Turkish barber even mean? (In the photo Hidden Woman.)

B.F.: Do you try to provoke the viewer’s powers of observation and concentration through a peculiar Easter egg hunting game, thereby declaring war on shallowness and superficiality? For example, Attention, maintain tension speaks about the openness of all the sensory organs and curiosity as preconditions for all thought and understanding. In one place we can read: On n’a pas fini d’avoir tout vu (‘We haven’t finished looking at everything’).

I.H.: I don’t expect anything from the viewer – they themselves know how they want to behave. However, the more keenly they look, the more they can uncover and experience, the more insights they will gain. The more the viewer submits, the more they will get back in return. I hope that the interrelationships of meanings in my works are understandable to all viewers, but it is also clear that there is not just one way of seeing. Everybody reads my texts differently, so therefore the possibility of open interpretation is an essential aspect of my works.

B.F.: So we are also talking about stimulating the viewer to reflect, to think for themselves.

I.H.: That’s what I offer, although it is not material for education, rather – the aim is to play, in order to reveal various ways of reading. People have very different interpretations of individual sentences or their interrelationships depending on their situation, personal experience, culture, religion and language.

B.F.: How do you work? Where do your sentences come from? Are they quotes from books, fragments from conversations with friends or derivations of proverbs and everyday expressions? Or have you truly created them from scratch?

I.H.: All of that is true. The texts come from my collection, which I have compiled by gathering texts from various contexts – everyday speech, advertisements, literature and philosophy. Advertising can be very philosophical, and sometimes the slogans are very good. This depends on the context in which they are read. In my works the context of the situation in which the respective sentence is placed is significant: it plays an important part in the process of creating meaning.

B.F.: So various levels of meaning develop in connection with the location.

I.H.: Yes, the meaning may shift in various directions, but mostly the question is about language itself, and then the meaning is selfreflexive. I respect both the direct messages in an advertisement as well as the interplay between slogans placed next to one another so they can be read in combination. A good example is the advertising slogan Wir planen Ihre Gedanken (‘We are planning your thoughts’): this sentence came from a design advertisement, but if you think about it carefully it can become threatening. Who is saying this and what thoughts are under discussion? This is Big Brother conducting our thoughts: in the case of the advertisement it is “only” the ad itself, and we don’t take it seriously, but the way it controls the mechanism of manipulation is impressive. I want to stress again that the stronger the sentences, the greater the possibility of leaving an impression on the viewer.

B.F.: In contrast to Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger, who work with similar existential and occasionally political slogans and who have developed almost unique visual styles, your messages are depicted in the most varied material forms: sculptures, installations, paintings, photographs. Not infrequently a link is forged between the meaning of the word and the material, which is partly contradictory and partly substantiation. An example of this tendency is the object Chimeron, a derivation of a chimera, a deceptive image, supplemented by a fairy-tale creature made from dark, heavy wood. An engaging contradiction arises between the intangibility of the deceptive image and the materiality of the wood.

I.H.: There are a number of differences between myself and Barbara Kruger or Jenny Holzer, because in their works the message is primary, while my inclination is toward language as such. For this reason more complex levels of meaning open up, and this is all enhanced by the material from which the two or three dimensional word is formed. Naturally, this material can be perceived visually or by touch, and it affects the overall image of what is written as well as the way it is read. There is a complex interrelationship between the packaging and content, the external image and the meaning.

B.F.: What is the significance of artistic aesthetics? Your objects are always very visually appealing and beautiful.

I.H.: The first impression of the object must be consciously powerful: large objects, bright colours, refined colour combinations. Previously I was a painter, and I still pay great attention in my work to visual imagery and the optical experience. The first visual seduction entices the viewer to spend longer viewing the work and to start reading the words or sentences. Initially the viewer encounters the external appearance before moving on to the content and meaning.

B.F.: Aesthetics and a beautiful surface as a bewitching narcotic.

I.H.: Yes, precisely, powerful expression. In our overcrowded world, in order to attract attention we need to be cunning and to use various resources.

B.F.: Previously you were a graphic artist, but now you use your technical skills to infiltrate the logic of advertising in order to transform accidentally encountered messages into literary, philosophical or existential comments that have the power to move us if we notice them and surrender to them. What do you think of the relationship between the direct, unambiguous forms of communication used in advertising and the indirect, polysemantic, veiled impulses of the forms of artistic expression which are more thoughtprovoking?

I.H.: It is the viewer’s job to find their way through these jungles of meaning. It is quite easy to notice and read an advertisement in its surrounding environment. We don’t think about it much since the text directly indicates a product or service. Unlike with advertising effects, my texts must project intellectual assets encompassed in broader interrelationships. But you can also find philosophical thought in advertising, for example, The world is our invention, which we discussed earlier. Of course, in an artistic context the viewer perceives advertising text differently than on the street. Both the expectations and the type of attention are different.

B.F.: So the text becomes a kind of ready-made art? It is declared to be a work of art, decontextualizing everyday life and transforming it in the artistic context?

I.H.: This is the case in terms of the sequence of events, but they aren’t really ready-made, because they are manipulated and changed much more.

B.F.: So they are ready-made preparations?

I.H.: Yes, you could call them that.

B.F.: You’ve been living abroad for about 30 years, first in Amsterdam and then, after the wall came down, in Berlin. Does your constant moving around and living the insecure life of an artist affect your work?

I.H.: I seek challenges, and I like cities and an urban environment where there is a lot to see, because a lot happens on the street. I think that we tend to find what we like because we go looking for it. We choose the thing that we allow to influence us.

B.F.: Did I ask the “right” questions?

I.H.: Since it is not possible to connect the explanation with something that is truly clear to someone receiving an explanation, there are no such things as clear explanations.

B.F.: So now we could start talking again about deceptions and illusory images.

I.H.: Yes, because “it’s not what you think”!

Translator into English: Filips Birzulis