The tormented Body, the double I

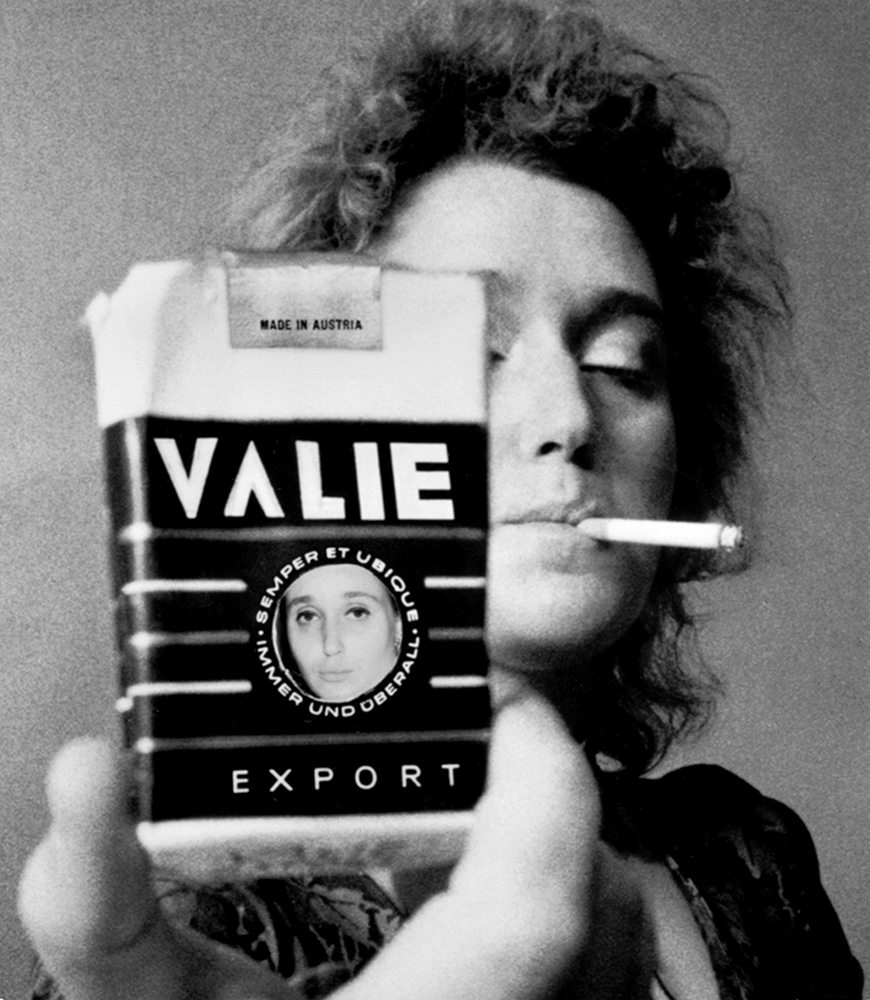

VALIE EXPORT is everywhere: she speaks to us, she captivates us with her intensive gaze, she takes a man moving on four legs for a walk through the streets on a leash, she sits with her naked genitals and wild hair on a chair and threatens us with a Kalashnikov, she performs a poem with her hands and she challenges us to a virtual Ping- Pong match. “VALIE EXPORT” is a pseudonym, a construction, a label: that’s understandable through the stamp with her circled name that brands all the artist’s documents, to give them – ironically – a validity seal for posterity. “VALIE EXPORT” is the artistic alter ego, the mirrored “I” of Waltraud Lehner, who first saw the light of day in 1940 in Linz.

The show at Kunsthaus Bregenz with the meaningful title Archive expands the whole artistic creation of the Austrian conceptual artist over the three square-shaped floors in the Zumthor-Cube. The never-ending ice-cold concrete stairs lead us to the space, where the archive of the artist has been opened for the first time to the public. In more than fifty white display cabinets one can marvel at the incredibly productive work of the Linzer artist, since their genesis, in a huge mass of conceptional papers, sketches and photographs. The observers dive into a sort of “full-immersion”, into the mental universe of one of the undoubtedly most important conceptual and performance artists of the 20th century, to participate in the production process, to have a look into the construction of a never-ending thought- and visual translation system.

On the second floor, the exhibition passes over to photo series and a space-filling installation, while on the last floor we are totally overwhelmed by the mass of video and film installations, in such a way that we become incapable of deciding in which direction to look first. The pieces of art on the second and third floor are visibly realisations of the conceptional ideas displayed in the showcases on the first floor, a fact which provokes a question about the possibility of deeper investigation: the red thread must be found again and again, which means the artworks have to be connected mentally in a laborious way with their corresponding concepts, seen before on the other level. The decision to classify the spaces corresponding to the categories of the documents they contain can be interpreted that priority was given to the aesthetics instead of sustaining the understanding process of contents and concepts. Of course, it looks “cleaner” if all the white showcases are set out on the same floor and all the film projections on the other. But they could have thought to show every topic and each piece of art from the beginning of its generating process, through sketches and texts, until its realisation, one next to the other: in that way, the public would have been accompanied in the process of decodification towards a possible interpretation of the meaning. Aesthetics versus didactics, beauty versus understanding, a well-known dilemma which here probably has been decided in favour of the aesthetics of space and to the detriment of clarification of contents. The effect could be that the rich treasure of EXPORT’s archive, put on view to the public for the first time, cannot really be explored to its maximum, and that a deeper access to the interpretation of the artworks may have been made more difficult rather than easier.

The longer one goes through the exhibition and gets confronted with the complex questions the artist has been investigating for almost fifty years, the clearer and clearer it becomes that the creation of a pseudonym is an indispensable aspect of her artistic strategy. “VALIE EXPORT” doesn’t denote the individual Waltraud Lehner anymore, but the universal species “woman”; she turns into the personification of the female gender as such. The body of the artist becomes a metaphor for the internal and external condition of all women, their lack of power, their social position. Setting her body in scene, VALIE EXPORT translates political mechanisms and the gender-specific status quo into strongly eloquent, simple and clear images. Through these purified representations the artist questions dominant matters, without ever putting on blinkers such as ideologies, or fixed and inflexible mental attitudes. On the contrary. The huge merit of VALIE EXPORT compared to other fellow campaigners is, without any doubt, her enormous ability for subtle humour and self-irony: that’s why her works maintain a genius easiness, even though they treat quite heavy topics.

In the world famous performance Aktionshose: Genitalpanik (‘Action Pants: Genital Panic’) from 1969 (which was performed again by Marina Abramovic at the New York Guggenheim in 2005), the artist presents herself wearing specially elaborated jeans, from which she has cut out a round hole of about ten centimeters just between the legs, at the crotch where the vulva is exhibited in great evidence. The artist is armed with a Kalashnikov that she is tampering with. This action indicates in a quite immediate way the social reduction of women to being sexual objects, and on the other hand their potential dangerousness and disposition to self-defence: the only part that is of interest and must be functional are the genitals, which the artist exhibits very directly, “framed” by the cut out pants. That means, on the other hand, that all the other qualities such as intelligence, cultural level or professional abilities don’t have any social relevance, or rather they only play a role among the male part of society.

In the performance Aus der Mappe der Hundigkeiten (‘From the Portfolio of Doggedness’), 1968, VALIE EXPORT takes the artist and media theorist Peter Weibel – on all fours and tied to a leash – for a walk through the streets of Vienna. With this spectacular intervention in the public space, the artist underlines in a very efficient way her idea of men: they are similar to dogs, obsessed by animal instincts, barking and beating creatures, whose cultural interests are not very distant from the physical needs of the quadruped.

In the same year, the Tapp und Tastkino (‘Touch Cinema’) was produced, in which Miss EXPORT buckles to her upper body a box with two openings, through which men are allowed to touch her breasts for half a minute. For the artist, “The woman is a central matter of the film. But the film must get out of the cinema, to be brought to the people. That’s better than the usual products of commercial film. The commercial films offer surrogates, we offer something real.” (1) Similarly as in Genitalpanik, the object of social desire is exhibited publicly and so the reduction of the female to an object is ironically underlined, in order to obtain the opposite of the situation. Men react with shame-filled laughter and demonstrate a certain shyness, exhibiting publicly their secret – even if “socially accepted” – fantasies.

In the photo series Body Configurations, which the artist has continued since the 1970s, she integrates her own body into the context of public space by adapting it to the given forms. The titles of the single photographs are quite meaningful: “Encirclement”, “Insertion”, “Fitting In” (Einkreisung, Einfügung, Einordnung, Einpassung). The woman wraps inserts herself into the existing order, adjusts herself to the laws and norms of society, fits streamlinedly into her role, without any resistance, ever.

In the body performance Hyperbulie (1973), from which the exhibition in Bregenz shows a black and white video, the artist crawls naked between two electrically charged wires, forward and backward,

bumping regularly with the face and the body into the electric fence, being beaten at every touch with an electric shock. This time, women are compared with cows, imprisoned and punished at each attempt to escape by an electric shock. Evidently females are, similarly as in Genitalpanik or Touch-Cinema, brutally reduced to their function of reproduction.

Pain is a recurring subject in EXPORT’s investigations and plays an important role in the representation of internal and external states of mind. However, hurt is not only generated by external social

situations, but in part integrated within our selves, in our being, and can bring us to forms of mortification. Self-mutilation as a reaction to external violence. About the “coming-to-one’s-self” of the experience of pain, the artist explains: “The cuts in the skin aren’t mortal anymore, but are openings to the intimate, to the innermost skin of the vessels, to ourselves.” (2)

One in this direction emblematic photograph is We are prisoners of our own selves (‘Wir sind Gefangene unserer Selbst’), where we see the artist behind some black bars. Oppressed people are – after that – a part of the system of oppression and internalize the mechanisms of power into themselves. Another example which demonstrates the same kind of functioning is Body Sign Action (1970), where VALIE EXPORT tattoos a garter into her thigh: a symbol of the dictate for females – to be sexy and beautiful. On the other hand, males are seen as shadow boxers, as Splitscreen-Solipsismus demonstrates so well: on the wall beside the corner, the artist mounts a mirror which redoubles the picture of the boxer on the other side. That means the boxer is fighting against himself, against his own mirror image, in reality against a mirage.

In later years, VALIE EXPORT’s creation has evolved more and more in the direction of weighty existential topics, and where violence against one’s own body reflects the extrinsic violence of power. In the film …Remote…Remote… from 1973, EXPORT scrapes at her fingers with a cutter and then immerses her bloody hands in a milk bath. Often, the effect of power is represented by the duplication of the picture (…Remote…Remote…) or by false mirroring, and with this, the artist divides the world in two parts: one of actors and the other of victims. In the feature Invisible Adversaries (‘Der unsichtbare Gegner’) from the year 1976, the main protagonist believes in the existence of the Hyksos, aliens that occupy the human brain and manipulate mankind from there. The effect of this manipulation is made visible by strange things happening, such as, for instance, Anna applying her lipstick only in the reflection of the mirror, while the “real” actress points her gaze in a completely different direction, lost in her thoughts, a prisoner in her total inertness. The doubling of the world or rather its falling apart is pointed out, too, by visual transitions. Real – coloured – female bodies lie on black and white photographs; Renaissance paintings (Piero della Francesca, Botticelli, Michelangelo) are reinterpreted in photography and the two versions projected one over the other. Woman as Madonna, an idealised picture of virginity. But the reality is different. Our bodies are tortured and injured, our mind tormented and ridden by fears. Anna dreams – physically in her bed, with skates on her feet – that she’s walking through the city – still wearing skates – in a regular, loud rhythm, step after step. At a certain point, she will cut her thigh with the blades in an unbearably long-lasting scene, and finally we see her skates from a very near point of view, turning pirouettes in eternal circles and carving blood red roundabouts in the white ice.

“The power of the impotent is the silence” (“Die Macht der Ohnmächtigen ist das Schweigen”), a voice offscreen exclaims in Invisible Adversaries, but VALIE EXPORT won’t be silent, even if she doesn’t talk much. Her language is the picture, she speaks with memorable depictions of powerful situations, which describe – as a metaphor – existing facts to denounce.

Reality is double, at least, but worlds of fantasy, false mirroring, transitions, adaptations and shadow-boxing aren’t enough to understand the world around us. Our perception must be thought of as a

multiple system: our body is tridimensional and able to “see” in all directions: in front, behind, upwards and downwards. In Adjungierte Dislokationen (‘Adjoined Dislocations’), an installation with three film projections produced between 1970 and 1979, the conceptual artist moves with two film cameras (one on the belly, the other on the back) through the public space, moving her top forwards and backwards. During the triple projection, observers see the same movement at the same time in three different versions and points of view: the first picture shows VALIE EXPORT walking around with the two cameras attached to her body and beside it, in a smaller size, are projected the two results of the two cameras she carried with her. The stupefying effect of this installation is that the three pictures are totally different and don’t seem to have anything in common, neither the aesthetics nor the subjects they present to be seen. They seem dislocated in time and space, and in this way create a strong visual contradiction. The Austrian artist demonstrates here, in a convincing way, that there is not one reality, but countless realities, as many as there are pairs of eyes able to see – or better – cameras to be pointed!

VALIE EXPORT invites us to learn how to deal with our multiple reality, without necessarily eradicating all the contradictions. In her room-filling installation Fragmente der Bilder einer Berührung (‘Fragments of pictures of contact’,1994), which occupies the whole second floor in the exhibition in Bregenz, burning electric lamps are immersed in glass bottles containing milk, water or oil, reminiscent of the rhythm of a derrick, moving regularly up and down. Electric power comes here in direct contact with three of the most essential liquids for human survival: surprisingly, the two spider enemies – electric power and liquids – seem to function together without any problem.

While in the earlier works the social differences have been evidenced in their most naked and strongest contrasts, and have been – by doing so – heavily underlined, VALIE EXPORT over time seems to have gradually become more conciliatory. But even if the contradictory parts have learnt to coexist, and the different elements have learnt to interact, Waltraut Lehner hasn’t lost anything of her acute attention, precise observation and tense radicality. She just paints now, except in black and white, more and more also with the whole range of gray tones. And that’s okay like this.

Barbara Fässler

(1) From: Peter Hajek. von Film zu Film, ‘Kurier’, 12 November 1968

(2) Documentation on Austria’s participation in the Venice Biennale, 1980