Miraculous Knowledge Factory in Images

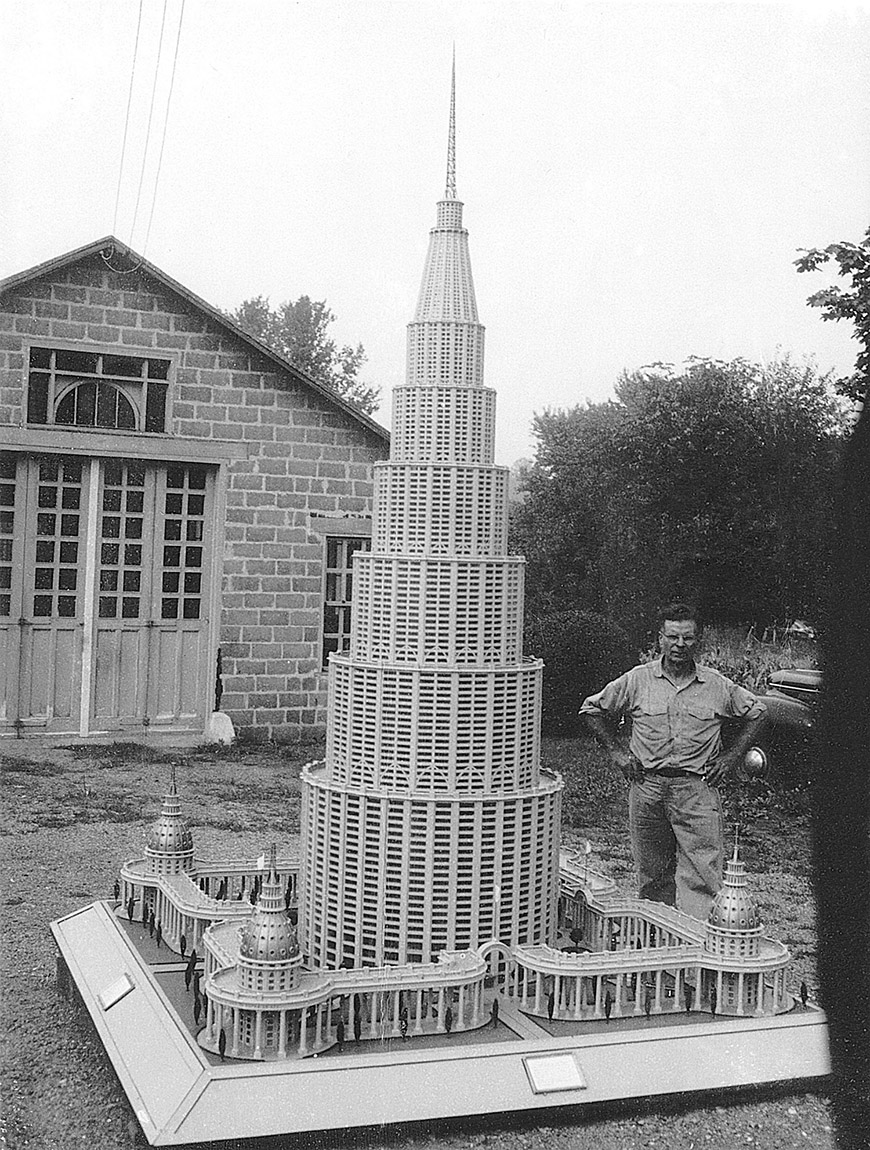

In a Skype conversation with Massimiliano Gioni (born in 1973), he tells me about his exhibition The Encyclopedic Palace at the Venice Biennale 55th International Art Exhibition. The initial impetus for it was provided by Marino Auriti’s project which – though patented – turned out to be impossible and came to nothing: the American mechanic and autodidact of Italian descent had hoped to construct a tower for storing all of humanity’s knowledge. Like Noah’s Ark, meant to save all knowledge from disappearing and being forgotten, Gioni’s biennale investigates the fruits of the imagination that combine knowledge with images, and departs for unknown lands where autodidacts, amateurs and outsiders live with their fantastic, phantasmagorical, irrational creative works. We’re going to rummage through the globalized world’s Wunderkammer or collection of curios, which can shake up Eurocentric, rational geography, reaching as far as the territories of the shamans which already border on the irrational. Any attempt to talk about the world as a whole becomes nightmarish and is destined for the same failure as the Encyclopedic Palace; basically it should be said that every biennale is this kind of attempt and each biennale’s curator, covered in perspiration, rolls his stone up the mountain…

Barbara Fässler: Good day, I’m happy meet you face to face and thank you for agreeing to the interview. I have to start with some words of appreciation for the huge job that you’ve started…

Massimiliano Gioni: Thank you! Can we speak informally?

B.F.: Gladly. I’d like to speak conceptually about your biennale project, especially the relationship between art and knowledge which touches on an important question in philosophical history, namely, the role of the senses and the mind in the cognitive process, a question on which the empiricists and rationalists are divided. But recently a growing interest can also be noticed about this in the art field, for example, Bice Curiger’s 2011 Biennale with the title ILLUMInazioni (1) cited enlightenment, and as part of Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev’s dOCUMENTA (13), situations were created in which art overlapped with knowledge, at the centre of which was an extremely tight space called the brain and packed with various significant objects and works. The brain is also portrayed in your biennale logo… This theme seems very current to me, and I’d like to understand how you look at all of this, and how your “knowledge theory” operates.

M.G.: (Laughing) Actually I don’t think that we can talk about my “knowledge theory”, I am more interested in the opportunity of taking a look at artists and their works as a method which brings us closer to knowledge. To put it more simply, I wanted this exhibition to reflect a variety of real problems. On the one hand, so that we can see the desire for knowledge, but at the exact moment when it becomes almost a nightmare or paranoia and turns into a kind of madness. If you want to know everything, you’ll lose your balance. On the other hand, the word immaginazione [imagination], for example, shows a close etymological connection between knowledge and imagine [image], namely, the idea is that our minds develop and operate in an image mode. One of the exhibition’s basic premises is that cognition is in pictures, images help us to imagine what we can’t see, to conceptualize the abstract. Images and imagination serve cognition and allow us to find out about what appears impossible or is located outside the borders of the cognizable. Here I should add that in many respects the exhibition is also connected with the surrealist tradition and the concept of the fantastic. Thirdly, one more aspect is connected with how we view these searches – we try to take in the widest possible field of vision, trying to keep in view not just artists and writers, but also marginal figures, the so-called amateurs, autodidacts or outsiders. I’d like to make us think about the definition of art, which risks being too narrow if it only applies to professional artists and excludes other episodic points of view.

B.F.: Auriti’s Encyclopedic Palace reminds one a little of an atlas, and of course, also an encyclopaedia, Malraux’s “imaginary museum”, Richter’s “Atlantis”, but, if we take some older examples, also the Tower of Babel and Tatlin’s tower which was dedicated to the Communist Third International. In brief, many different attempts to collect humanity’s knowledge together in some way can be found in history. Diderot maintains that the purpose of the encyclopaedia is to collect knowledge in one place and to pass it on to the next generation, as “we should not die without having rendered a service to the human race in the future years to come”.

M.G.: First of all we have to take a step back, because, in quoting Diderot, it is important to emphasize that the exhibition is called The Encyclopedic Palace. However, in its own way, it contains nothing of an encyclopaedia of enlightenment, nor does the title of Bice Curiger’s exhibition you mentioned, either. It is more an exhibition where attempts at cognition can be viewed in baroque, mediaeval versions, namely, as encyclopaedias in which facts, legends and myths are wound together and the concept of knowledge is more along the path of association which actually is also the contemporary experience of knowledge: the exhibition not so much shows how it is possible to properly systematize knowledge, but rather – the kinds of means, and the kinds of channels we use to communicate. In my view, the exhibition speaks about certain irrational motifs, not about something like a new enlightenment, so to speak.

B.F.: Should we look for harsh criticism of the current crisis, especially in relation to Italy, in The Encyclopedic Palace?

M.G.: When working on an exhibition of this scale, I always try to find arguments which will take us a little further than immediate, directly accessible reality. I like it when references to contemporaneity can also be read “against the light”, but I still hope that the arguments posed in this exhibition will rise, even a little, above this reality and will unravel the knots in which our artists and the average person have been caught up more than once. It’s clear that an exhibition about knowledge and knowledge through images is very real – at least I think so – because it shows the conditions in which we all live. We live in a so-called image and knowledge society, where information, economics and power are ever more tightly bound together. In the reflection about the role of autodidacts and amateurs, the exhibition also focuses on the criteria for inclusion and exclusion. Who has the right to exhibit, and who doesn’t? And, if you ask whether the exhibition specifically refers to the state of Italy’s economy, I’m inclined towards a negative answer, even if one can see works in it that touch on some related problems, for example, Marco Paolini’s performances which portend of disappearing professions, or Rossella Biscotti’s work where she works with female prisoners, asking them to talk about their dreams. So there are works which overlap with reality, however, I hope that it’s not face-to-face, but across the diagonal.

B.F.: Then perhaps a desperate attempt to manufacture a Noah’s Ark for the knowledge of humanity can be seen here?

M.G.: Noah’s Ark as an image has served us as a source of inspiration, as I’d imagined the Arsenale as a place where ships are made and also as a place where the idea of the miraculous was born. The idea of the miraculous and fantastic, connected with Venice, and the Arsenale in particular, which was once called the La fabbrica delle meraviglie (Factory of Miracles), occurred in the 16th century against the background of the geographic expansion fostered by colonization. This era of miracles returned in the 20th century with Borges and all of this fantastic and phantasmagorical tradition, which I thought would be interesting to investigate.

B.F.: You once maintained that you place personal cosmology and cognitive nightmares in opposition to an all-encompassing dream about universal knowledge which “tries in vain to fashion an image of the world that will capture its infinite variety and richness”. Are irrational, nightmarish and crazy images able to lead us out of the world’s impasses, muddled by an overload of information? Art, therefore, has a utopian, social or educational objective? If so, then what sort?

M.G.: This irrational aspect that you mention, which I wanted to see and on which more than one of the exhibited works focuses, becomes revealed in an individual’s interaction with this sea of information, mare magnum. Even in the most nightmarish instances, situations arise where the individual arrives in the midst of a flow of images – there are examples from which we can learn about how this sea of information can be navigated. I say this, while looking at you and my computer at the same time. Maybe the space needed by digital society makes us empathize with the collector, imagining him sorting his Wunderkammer, where he places all the objects around him, on the one hand harbouring illusions that he is the master and decision-maker, but, on the other, historically living in an era where the centre is disappearing. The idea about the Wunderkammer’s miraculous, heterogeneous nature arises at the moment when a checkmate has been declared on Eurocentric geography and history. I hope that in some of these works you’ll be able to see this desperate attempt to manufacture an ark, and also an individual’s need to find themselves at the centre of an ever wider, more confused and less comprehensible world.

B.F.: What are the functions of art, then?

M.G.: Without number, aren’t they? I think that two points will crystallize out of this exhibition. One is art as the expression of our internal image externally, exteriorization. At the base of this is an entirely banal finding which never, however, stops surprising me, namely, that the location of images for a person is in the mind. The second point of support is Carl Gustav Jung’s book of dreams and visions, in which he sets forth his vision and internal images. The magic of art lies directly in encountering the types of images that for an instant seem exactly like the ones which we hold within ourselves. This type of experience often happens to us at the cinema, too, when the scenes on the screen resemble our dream images. The fact that we find them outside ourselves, comes over us like a mindboggling revelation. One aspect of the function of art is as follows: visualizing our internal images and making them visible. Insofar as the exhibition is tied up with various surreal figures and versions, it does encourage us in a way to rely on the fantastic, seeking in it not a sanctuary, but a field of action for the imagination. I think that today, when the world is increasingly preoccupied with images, the function of art is to help us define a new ecology of seeing and images – to be able, these days, to discern something in the thick of the many images, which involuntarily make everything unclear. Art can come to our assistance when we are trying to understand which images are worth keeping and which ones to throw in the rubbish bin. Obviously, art also has many other functions and simultaneously has no function at all – that’s also the most beautiful thing about art.

B.F.: We’ve been talking about the functions of art and images, and now I’d like to ask you, as a curator who is the creator of images. Returning to the subject of The Encyclopedic Palace – in creating an archive, we always make a choice. Do you choose artists and works, and with the help of all the attendant elements selecting the exhibition’s overall design as well, or not?

M.G.: Yes.

B.F.: The archive itself, one would think, is like a grid that determines the reality, resolving what should be kept and what will be forgotten. You’ll be giving the art of the next few years a new face. How do you view this Encyclopedic Palace which you’re helping to construct?

M.G.: You know, the choice in favour of The Encyclopedic Palace as a name and the reference to Auriti is also a self-critical commentary on the biennale, and also about me – it’s true, it should be said that the exhibitions aren’t organized so as to talk about me. Auriti’s The Encyclopedic Palace is a failed project, no, it’s a wonderful project, but a flop, a typical plan which is definitely destined to remain at the planning stage. It seemed to me that that alone would be like an antidote against the idea of universal knowledge. I thought it important to make one thing clear – I’m not organizing an exhibition which would declare: see, here’s everything that you can possibly know, come and have a look. The exhibition is about attempts to get to all-encompassing knowledge, but also about attempts which have suffered failure, if you so wish.

B.F.: Of course…

M.G.: In a way we admit that it’s not possible to expect of the Venice Biennale that its narrative would encompass the whole world. I wanted to point that out clearly because the biennale is an exhibition which more than others – having such a long history – is rooted directly in this 19th century idea of universalism, one which has inspired world exhibitions. Having made my choice, I also wanted to immediately awaken suspicions about the impossibility of such a form of knowledge, about the fact that it is always partly and inescapably destined for failure. The second, more autobiographical aspect is that I, too, felt a little like some kind of Auriti, standing before an unrealizable task. A kind of autodidact, thrown under a kind of spotlight of fame through this exhibition, which strangely also corresponds with how I feel – as a curator, and perhaps also in my daily life. In brief, like an autodidact who is always found on the border of cracking up, trying to comprehend everything there is to know.

B.F.: What is there in your palace? Accidentally found objects or those chosen according to rational criteria? What labels will you be putting on the drawers of the furniture in your palace?

M.G.: First of all I have to say that the palace is not yet ready (laughs), possibly, it should have been much larger, so maybe it’s better that it’s not ready yet. The central pavilion, especially, where we’ll find a reflection about the image within us: a dream, a vision about the correspondences between the microcosm and macrocosm. Every paranoid person knows that coincidence doesn’t tend to occur, or that everything is a coincidence and nothing else.

It should be stated that the Arsenale, in turn, is dedicated to the artist who is trying to put order into the world. Initially, there is a reflection about the forms of nature, the artist tries to portray trees, to reveal the plant code, the secret language of flowers and seashells. An attempt to look at the world with the eyes of an innocent, again and again ending up in a quandary, and then, very slowly, the exhibition gains strength, if it could be put this way. There follows a string of works in which the artist tests his strength against the contemporary society of images, namely, with information and digital culture, and new “artefacts”, artificialia (2). At the centre of the Arsenale there will be an exhibition organized by Cindy Sherman which touches on one of the main aspects of the problem of image, namely, the portrayal of our bodies and faces.

B.F.: While watching the press conference video and the illustrations you’ve created, I noticed that many of the works are actually images, two-dimensional creations.

M.G.: Yes.

B.F.: It seems that you have focussed more on the message, the story, as you said previously, the imagination, in a way madness as well, internal visions and not, shall we say, more formal art categories. Do we have to imagine a biennale full of images hanging on the walls, or will there also still be spatially, physically tactile works, performances?

M.G.: First of all it should be noted – it’s true, as you point out, that there’ll be many two-dimensional works hanging on the walls at the exhibition. In this way, the exhibition to a certain extent will be very traditional, but there are a number of reasons for this. Firstly, the exhibition is about the aspect, which is connected with inwardness. For example, drawing here has a very important role, more important even than painting – the act of drawing resembles a feverish recounting or aggregation of thoughts, it is akin to the concept of automatic writing. Spatially, a drawing is almost a direct extension of our imagination, and its presence will be felt throughout. Maybe because the exhibition is a contemplation about images, but a different matrix already operates beyond the two-dimensionality in the portrayal – the mask, template and sculpture, let’s say the hyperreal. Another “supporting element” is the book. Jung’s book, and artists who collect or create books, or also think about image space expressed through books or diaries, should be mentioned. The book is regarded as the topos and sanctuary of the projection of our ideas, and also as a place from which the journeys of flights of fancy begin.

Of course, I hope that the exhibition will have physical power as a whole, even though often enough this is made up of a conglomeration of individual objects. However, I give priority not to monumental exhibits, but rather the sense of greatness which is created in its own way by the repetition of many small things. Also because I wished to distance myself a little from the prevalent theatricality of the biennale…

B.F.:… from the scenographic, yes.

M.G.: The museum is this exhibition’s point of reference, as I’m also looking for a more intimate dimension. I don’t know if I’ll succeed at the Arsenale – speaking of the Arsenale’s architecture, one of the greatest tasks was the arranging of the space, setting it up so that an intimate experience would be possible when in contact with exhibits which are smaller in scale. However, I undoubtedly hope that there will also be “more physical” moments, for example, in a range of works in which the human body is used, in performance. In my view, performance is the same type of medium as all the others, and they are all included in the exhibition. A kind of imaginary language leads us to an exhibition. The idea that a universal language exists which has reached perfection, it can be felt in many works, for example, in Steve McQueen’s work, in John Bock’s performances where imaginary languages can often be heard, in Tino Sehgal’s work and in many others, in Xul Solar’s (3) books etc.

B.F.: You just mentioned the concept of the museum. In an interview to Vogue magazine you said that a curator isn’t a selfcontained artist, but is forced to collaborate with other artists, and where necessary show a readiness to make mistakes together with them. For me, a museum to some degree is still associated with a mausoleum, a place where to store something forever. For you, this large project has suddenly awoken an interest in conservation. Can we still expect that you and the artists will be making mistakes together?

M.G.: I hope there will be many such moments… Previously I mentioned Tino Sehgal. To get his work together for six months meant gathering together a truly crazy team of participants in the most direct meaning of the word, because we’ll be working with hundreds of people working in shifts. Another work, curated by Ragnar Kjartansson, will require dozens of musicians, who will be playing for six consecutive months. The length of the biennale creates quite insane challenges. I understand what you wanted to say with regard to the museum as a mausoleum, but in reality, I, at least for the moment – despite the fact that the museum idea has gone slightly out of fashion – think about a museum as a kind of magicians’ place. It is a place which isn’t an annual art market or a gallery, nor even a diverting entertainment of which there’s no shortage nowadays, but rather a sort of old museum, perhaps a little dusty, where alongside less significant works one can see masterpieces. You could say this kind of museum to a certain degree is much closer to the Wunderkammer, namely, it’s a museum in which the irrational has been mixed up with the seeds of rationalism. Roger Caillois, the artist-writer, who has penned books about the sacred, provides a good example: in one of them he tells us about how, when the Seoul Museum was being opened, he was surprised that the viewers on arriving at the exhibition hall and seeing a statue of Buddha didn’t look at it as a work of art, but instead fell to their knees as if they’d entered a temple. This understanding of a museum – a place where one can enjoy works of art, at the same time also evaluating their sacred dimension with all the precautionary steps which the use of this word demands – here, see, stating it briefly, is something I consider interesting, and I’m not saying that in the hope that the public will fall to its knees before some sculpture, but rather that everyone at the biennale would be overtaken by the experience not of a mausoleum, but one of magic. I really hope this happens.

B.F.: How will your biennale differ from those with which you’re already familiar, and also Bonami’s (4) biennale, where you also contributed to the development?

M.G.: Speaking of previous biennales… You know, this biennale continues my investigations, the research that I’ve been doing for a while now and which is reflected in many of the other exhibitions I have curated. In comparison to previous biennales, I think that the most significant difference, on the one hand, will be the broad historical spectrum, as it embraces the period from the beginning of the 20th century until today with a few citations from the 19th century as well. On the other hand, amateurs or outsiders will also be represented, and that, it seems to me, will also be the distinctive aspect, the culmination of this trend which not only I acknowledge, but which in recent years has earned ever growing attention.

B.F.: How would you like the coming generations to remember your biennale?

M.G.: How will it be remembered? Judging from the newspaper headlines (laughs), an outsider biennale is currently being created and there’s nothing wrong with that, either. I hope it will remain in memory… You know, I really put in a lot of effort to get an exhibition ready in which I could continue doing what I know how to do, but I tried not to take the easiest path. For example, I didn’t include any of the many artists with whom I’d worked previously in many exhibitions, that is, I tried to break away a little from my sphere of influence and circle of acquaintances. How will it be remembered… Well, there’s nothing to say that it will be remembered (laughs again). They say that a biennale is at its most beautiful two years later, when everybody is saying – the last one was more beautiful…

B.F.: It happens without even thinking about it!

M.G.: I hope that mine will be remembered in 2015 as a beautiful biennale (laughs).

B.F.: Thank you very much and let’s cross our fingers!

Barbara Fässler

Translated into English: Uldis Brūns

(1) Reading the title as two words running together, we get the meaning “enlightens the nation” (Italian – illumina nazioni).

(2) Items found in the studies of 16th century collectors were often divided into artificialia [artificial] and naturalia [natural], the first being man-made, artefacts, and the second – various natural things of beauty. Such a division, in the hybridization context of contemporary art, is obviously problematic.

(3) His real name was Óscar Agustín Alejandro Schulz Solari, (1887–1963) – an Argentine artist, sculptor, inventor of an imaginary language. His father Elmo Schulz was a Baltic German, born in Rīga.

(4) Francesco Bonami (born 1955) – Italian curator. In 2003, he directed the International Exhibition The Viewer’s Dictatorship (La dittatura dello spettatore) at the 50th Venice Art Biennale.